THE IS SHARED ONLINE

JOURNAL.

AUTHOR.MR.FELIX ATI-JOHN

ACADEMIC WRITING

SUBJECT - CONSERVATORHIP

LAWS IN ELDERLY OR OLDER PEOPLE HELP

AND ADULT PSYCHIATRY

SCOPE OF THIS

ACADEMIC WRITING

A-SOLVING A SPECIFIC PROBLEM

B-ACADEMIC WRITING TO THE LEARNING OF A DISCIPLINE SUCH AS

EDUCATION OR SOCIAL WORK

C-GOVERNMENT POLICY SUCH OF WELFARE OR HEALTH POLICY

THIS RESEARCH PAPER BECOMES NECESSARY PURSUANT OF

PROFESSIONAL OBLIGATIONS AND EXPRESSIONS WITH RESPECT

OF SOCIAL CONFORMS AND THE INTERNATIONAL LAW,

THIS WORK IS TITLED CONSERVATORHIP LAWS IN ELDERLY OR OLDER

PEOPLES HELP

AND ADULT PSYCHIATRY

.

CONCURRENT

VALIDITY

TO BE ABLE TO WRITE THIS WORK,A REVIEW STUDY WAS MADE AND

THESE BEING OF THE HOSPITAL,ELDERLY CARE NURSING HOME AND ALSO THE TEACHING

HOSPITAL AND TO COMPOSE THIS WRITING

,THE PROCEDURAL MEASURES OF LAW ORDER TO

AND FOR CONSERVATORSHIP IN A COURT IN FRANFURT AM MAIN GERMANY IN THE EUROPEAN

UNION WAS MADE IN AN APPLICATION BY THE AUTHOR OF THIS TRANSLATIONAL

RESEARCH WORK,USED HEREIN IN

PLACE OF COPYRIGHTS INFRINGMENT,PATENTS AND OTHERS.

A VISIT TO THE PSYCHIATRY HOSPITAL WIEL MUENSTER GERMANY IN

THE EUROPEAN UNION WAS ALSO MADE

PURSUANT OF THIS ACADEMIC WRITING

THOUGH THE TITLE OF THIS WORK IS CONSERVATORHIP LAWS IN

ELDERLY OR OLDER PEOPLES HELP

AND ADULT PSYCHIATRY

,BUT THE ASPECT OF

THIS WRITING COVERS ALSO USING OF FIX BELTS IN A HEALTH FACILITY ON

CLIENTS SAID TO BE GRAVELY DISABLED BUT HAVING THE RIGHT OF OCCUPANCY IN A

HEALTH FACILITY.

AUTORING AND PUBLISHING

VALIDITY OF HEALTH FACILITY WAS

MADE,AND OF THE CATEGORY OF HOSPITAL AND ELDERLY CARE NURSING HOME AND THE TEACHING

HOSPITAL BY THE AUTHOR

THIS LITERARY

COMPOSTION IS THE WORK OF AND IS MADE BY MR:FELIX ATI-JOHN FOR THE

PURPOSE AND IS AN ACADEMIC WRITING,RESEARCH AND HEALTH PROFESSIONAL

PUBLICATION

COPIES OF DOCUMENTS ATTACHED-

AMTS GERICHT

DOCUMNETS

EMPLOYERS WITNESS CERTIFICATE

OTHER PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATION

THIS ACADEMIC WRITING AND CONTENTS WORKS

FROM THE WIKIPEDIA LIBRARY,THE GERMAN

COURT

AND THE AUTHOR RESEARCH EVALUATION.

Systematic review

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the academic journal, see Systematic Reviews.

An understanding of systematic reviews, and how to implement them in practice, is becoming mandatory for all professionals involved in the delivery of health care. Besides health interventions, systematic reviews may concern clinical tests, public health interventions, social interventions, adverse effects, and economic evaluations.[3][4] Systematic reviews are not limited to medicine and are quite common in all other sciences where data are collected, published in the literature, and an assessment of methodological quality for a precisely defined subject would be helpful.[5]

Contents

[hide]Characteristics[edit]

A systematic review aims to provide an exhaustive summary of current literature relevant to a research question. The first step of a systematic review is a thorough search of the literature for relevant papers. The Methodology section of the review will list the databases and citation indexes searched, such as Web of Science, Embase, and PubMed, as well as any hand-searched individual journals. Next, the titles and the abstracts of the identified articles are checked against pre-determined criteria for eligibility and relevance. This list will always depend on the research problem. Each included study may be assigned an objective assessment of methodological quality preferably using a method conforming to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (the current guideline)[6] or the high quality standards of Cochrane collaboration.[7]Systematic reviews often, but not always, use statistical techniques (meta-analysis) to combine results of the eligible studies, or at least use scoring of the levels of evidence depending on the methodology used. An additional rater may be consulted to resolve any scoring differences between raters.[5] Systematic review is often applied in the biomedical or healthcare context, but it can be applied in any field of research. Groups like the Campbell Collaboration are promoting the use of systematic reviews in policy-making beyond just healthcare.

A systematic review uses an objective and transparent approach for research synthesis, with the aim of minimizing bias. While many systematic reviews are based on an explicit quantitative meta-analysis of available data, there are also qualitative reviews which adhere to standards for gathering, analyzing and reporting evidence.[8] The EPPI-Centre has been influential in developing methods for combining both qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews.[9] The PRISMA statement[10] suggests a standardized way to ensure a transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews, and is now required for this kind of research by more than 170 medical journals worldwide.[11]

Recent developments in systematic reviews include realist reviews,[12] and the meta-narrative approach.[13][14] These approaches try to overcome the problems of methodological and epistemological heterogeneity in the diverse literatures existing on some subjects.

Cochrane Collaboration[edit]

The Cochrane Collaboration is a group of over 31,000 specialists in healthcare who systematically review randomised trials of the effects of prevention, treatments and rehabilitation as well as health systems interventions. When appropriate, they also include the results of other types of research. Cochrane Reviews are published in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews section of the Cochrane Library. The 2010 impact factor for The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was 6.186, and it was ranked 10th in the “Medicine, General & Internal” category.[15] There are six types of Cochrane Review:[16][17][18][19]- Intervention reviews assess the benefits and harms of interventions used in healthcare and health policy.

- Diagnostic test accuracy reviews assess how well a diagnostic test performs in diagnosing and detecting a particular disease.

- Methodology reviews address issues relevant to how systematic reviews and clinical trials are conducted and reported.

- Qualitative reviews synthesize qualitative and quantitative evidence to address questions on aspects other than effectiveness.[8]

- Prognosis reviews address the probable course or future outcome(s) of people with a health problem.

- Overviews of Systematic Reviews (OoRs) are a new type of study in order to compile multiple evidence from systematic reviews into a single document that is accessible and useful to serve as a friendly front end for the Cochrane Collaboration with regard to healthcare decision-making.

- Defining the review question(s) and developing criteria for including studies

- Searching for studies

- Selecting studies and collecting data

- Assessing risk of bias in included studies

- Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses

- Addressing reporting biases

- Presenting results and "summary of findings" tables

- Interpreting results and drawing conclusions

Strengths and weaknesses[edit]

While systematic reviews are regarded as the strongest form of medical evidence, a review of 300 studies found that not all systematic reviews were equally reliable, and that their reporting can be improved by a universally agreed upon set of standards and guidelines.[22] A further study by the same group found that of 100 systematic reviews monitored, 7% needed updating at the time of publication, another 4% within a year, and another 11% within 2 years; this figure was higher in rapidly changing fields of medicine, especially cardiovascular medicine.[23] A 2003 study suggested that extending searches beyond major databases, perhaps into grey literature, would increase the effectiveness of reviews.[24]Roberts and colleagues highlighted the problems with systematic reviews, particularly those conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration, noting that published reviews are often biased, out of date and excessively long.[25] They criticized Cochrane reviews as not being sufficiently critical in the selection of trials and including too many of low quality. They proposed several solutions, including limiting studies in meta-analyses and reviews to registered clinical trials, requiring that original data be made available for statistical checking (a proposal that had been previously made by other researchers[26]), paying greater attention to sample size estimates, and eliminating dependence on only published data.

Some of these difficulties were noted early on as described by Altman: "much poor research arises because researchers feel compelled for career reasons to carry out research that they are ill equipped to perform, and nobody stops them."[27] Methodological limitations of meta-analysis have also been noted.[28] Another concern is that the methods used to conduct a systematic review are sometimes changed once researchers see the available trials they are going to include.[29] Bloggers have described retractions of systematic reviews and published reports of studies included in published systematic reviews.[30][31][32]

Systematic reviews are increasingly prevalent in other fields, such as international development research.[33] Subsequently, a number of donors – most notably the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and AusAid – are focusing more attention and resources on testing the appropriateness of systematic reviews in assessing the impacts of development and humanitarian interventions.[33]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ "systematic review". GET-IT glossary. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Jump up ^ "What is EBM?". Centre for Evidence Based Medicine. 2009-11-20. Archived from the original on 2011-04-06. Retrieved 2011-06-17.

- Jump up ^ Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: University of York, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2008. ISBN 978-1-900640-47-3. Retrieved 2011-06-17.[page needed]

- Jump up ^ Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences. Wiley Blackwell, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Herman J. Ader; Gideon J. Mellenbergh; David J. Hand (2008). "Methodological quality". Advising on Research Methods: A consultant's companion. Johannes van Kessel Publishing. ISBN 978-90-79418-02-2.[page needed]

- Jump up ^ "PRISMA". Prisma-statement.org. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- Jump up ^ "Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions". Handbook.cochrane.org. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bearman, Margaret; Dawson, Phillip. "Qualitative synthesis and systematic review in health professions education". Medical Education 47 (3): 252–260. doi:10.1111/medu.12092.

- Jump up ^ Thomas, J.; Harden, A; Oakley, A; Oliver, S; Sutcliffe, K; Rees, R; Brunton, G; Kavanagh, J (2004). "Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews". BMJ 328 (7446): 1010–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7446.1010. PMC 404509. PMID 15105329.

- Jump up ^ Liberati, Alessandro; Altman, Douglas G.; Tetzlaff, Jennifer; Mulrow, Cynthia; Gøtzsche, Peter C.; Ioannidis, John P. A.; Clarke, Mike; Devereaux, P. J.; et al. (2009). "The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration". PLoS Medicine 6 (7): e1000100. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. PMC 2707010. PMID 19621070.

- Jump up ^ Endorsing PRISMA. http://www.prisma-statement.org/endorsers.htm.

- Jump up ^ Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. (2005). "Realist review - a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions". Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10: 21–34. doi:10.1258/1355819054308530.

- Jump up ^ MacFarlane, Fraser; Kyriakidou, Olivia; Bate, Paul; Peacock, Richard; Greenhalgh, Trisha (2005). Diffusion of Innovations in Health Service Organisations: A Systematic Literature. Studies in Urban and Social Change. Blackwell Publishing Professional. ISBN 0-7279-1869-9.[page needed]

- Jump up ^ Greenhalgh, Trisha; Potts, Henry W.W.; Wong, Geoff; Bark, Pippa; Swinglehurst, Deborah (2009). "Tensions and Paradoxes in Electronic Patient Record Research: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Meta-narrative Method". Milbank Quarterly 87 (4): 729–88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00578.x. JSTOR 25593645. PMC 2888022. PMID 20021585.

- Jump up ^ The Cochrane Library. 2010 impact factor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). Frequently asked questions. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- Jump up ^ Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

- Jump up ^ The Cochrane Library

- Jump up ^ Silva V, Grande AJ, Carvalho AP, Martimbianco AL, Riera R (2014). "Overview of systematic reviews - a new type of study. Part II". Sao Paulo Med J. 133: 206–217. doi:10.1590/1516-3180.2013.8150015.

- Jump up ^ Silva V, Grande AJ, Martimbianco AL, Riera R, Carvalho AP (2012). "Overview of systematic reviews - a new type of study. part I: why and for whom?". Sao Paulo Med J. 130 (6): 398–404. doi:10.1590/S1516-31802012000600007%20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-17.

- Jump up ^ "Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR)". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Jump up ^ Moher, David; Tetzlaff, Jennifer; Tricco, Andrea C.; Sampson, Margaret; Altman, Douglas G. (2007). "Epidemiology and Reporting Characteristics of Systematic Reviews". PLoS Medicine 4 (3): e78. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040078. PMC 1831728. PMID 17388659.

- Jump up ^ Shojania, Kaveh G.; Sampson, Margaret; Ansari, Mohammed T.; Ji, Jun; Doucette, Steve; Moher, David (2007). "How Quickly Do Systematic Reviews Go Out of Date? A Survival Analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine 147 (4): 224–33. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-4-200708210-00179. PMID 17638714.

- Jump up ^ Savoie, Isabelle; Helmer, Diane; Green, Carolyn J.; Kazanjian, Arminée (2003). "Beyond Medline: reducing bias through extended systematic review search". International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 19 (1): 168–78. doi:10.1017/S0266462303000163. PMID 12701949.

- Jump up ^ Roberts, I; Ker, K; Edwards, P; Beecher, D; Manno, D; Sydenham, E (3 June 2015). "The knowledge system underpinning healthcare is not fit for purpose and must change.". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 350: h2463. doi:10.1136/bmj.h2463. PMID 26041754.

- Jump up ^ Masters, Ken (Dec 2014). "A new level of evidence: Systematic literature reviews (SLRs) with meta-analyses of directly-accessed data ("MA of DAD")". Medical Teacher 36 (12): 1080–1081. doi:10.3109/0142159x.2014.916790. PMID 24804915.

- Jump up ^ Altman, DG (29 January 1994). "The scandal of poor medical research.". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 308 (6924): 283–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.308.6924.283. PMID 8124111.

- Jump up ^ Shapiro, S (1 November 1994). "Meta-analysis/Shmeta-analysis.". American Journal of Epidemiology 140 (9): 771–8. PMID 7977286.

- Jump up ^ Page, MJ; McKenzie, JE; Kirkham, J; Dwan, K; Kramer, S; Green, S; Forbes, A (Oct 1, 2014). "Bias due to selective inclusion and reporting of outcomes and analyses in systematic reviews of randomised trials of healthcare interventions.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 10: MR000035. doi:10.1002/14651858.MR000035.pub2. PMID 25271098.

- Jump up ^ "Retraction Of Scientific Papers For Fraud Or Bias Is Just The Tip Of The Iceberg". IFL Science!. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Jump up ^ "Retraction and republication for Lancet Resp Med tracheostomy paper". Retraction Watch. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Jump up ^ "BioMed Central retracting 43 papers for fake peer review". Retraction Watch.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hagen-Zanker, Jessica; Duvendack, Maren; Mallett, Richard; Slater, Rachel; Carpenter, Samuel; Tromme, Mathieu (January 2012). "Making systematic reviews work for international development research". Overseas Development Institute.

External links[edit]

| Library resources about systematic review |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Systematic review. |

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York.

- Cochrane Collaboration

- Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), University of London

- MeSH: Review Literature—articles about the review process

- MeSH: Review [Publication Type] - limit search results to reviews

- PubMed search: "Review Literature" [MAJR]

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement, "an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses"

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nuisance

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the 1921 film, see The Nuisance. For statistics, see Nuisance parameter.

Nuisance (from archaic nocence, through Fr. noisance, nuisance, from Lat. nocere, "to hurt") is a common law tort. It means that which causes offence, annoyance, trouble or injury. A nuisance can be either public (also "common") or private. A public nuisance was defined by English scholar Sir J. F. Stephen as,"an act not warranted by law, or an omission to discharge a legal duty, which act or omission obstructs or causes inconvenience or damage to the public in the exercise of rights common to all Her Majesty's subjects".[1]Private nuisance is the interference with the right of specific people. Nuisance is one of the oldest causes of action known to the common law, with cases framed in nuisance going back almost to the beginning of recorded case law. Nuisance signifies that the "right of quiet enjoyment" is being disrupted to such a degree that a tort is being committed.

Contents

[hide]Definition[edit]

| Part of the common law series |

| Tort law |

|---|

| Intentional torts |

| Property torts |

| Defenses |

| Negligence |

| Liability torts |

| Nuisance |

| Dignitary torts |

| Economic torts |

| Liability and remedies |

| Duty to visitors |

| Other common law areas |

Legally, the term nuisance is traditionally used in three ways:

- to describe an activity or condition that is harmful or annoying to others (e.g., indecent conduct, a rubbish heap or a smoking chimney)

- to describe the harm caused by the before-mentioned activity or condition (e.g., loud noises or objectionable odors)

- to describe a legal liability that arises from the combination of the two.[2] However, the "interference" was not the result of a neighbor stealing land or trespassing on the land. Instead, it arose from activities taking place on another person's land that affected the enjoyment of that land.[3]

A public nuisance is an unreasonable interference with the public's right to property. It includes conduct that interferes with public health, safety, peace or convenience. The unreasonableness may be evidenced by statute, or by the nature of the act, including how long, and how bad, the effects of the activity may be.[4]

A private nuisance is simply a violation of one's use of quiet enjoyment of land. It doesn't include trespass.[5]

To be a nuisance, the level of interference must rise above the merely aesthetic. For example: if your neighbour paints their house purple, it may offend you; however, it doesn't rise to the level of nuisance. In most cases, normal uses of a property that can constitute quiet enjoyment cannot be restrained in nuisance either. For example, the sound of a crying baby may be annoying, but it is an expected part of quiet enjoyment of property and does not constitute a nuisance.

Any affected property owner has standing to sue for a private nuisance. If a nuisance is widespread enough, but yet has a public purpose, it is often treated at law as a public nuisance. Owners of interests in real property (whether owners, lessors, or holders of an easement or other interest) have standing only to bring private nuisance suits.

History and legal development of nuisance[edit]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the law of nuisance became difficult to administer, as competing property uses often posed a nuisance to each other, and the cost of litigation to settle the issue grew prohibitive. As such, most jurisdictions now have a system of land use planning (e.g. zoning) that describes what activities are acceptable in a given location. Zoning generally overrules nuisance. For example: if a factory is operating in an industrial zone, neighbours in the neighbouring residential zone can't make a claim in nuisance. Jurisdictions without zoning laws essentially leave land use to be determined by the laws concerning nuisance.Similarly, modern environmental laws are an adaptation of the doctrine of nuisance to modern complex societies, in that a person's use of his property may harmfully affect another's property, or person, far from the nuisance activity, and from causes not easily integrated into historic understandings of nuisance law.

Remedies[edit]

Under the common law, the only remedy for a nuisance was the payment of damages. However, with the development of the courts of equity, the remedy of an injunction became available to prevent a defendant from repeating the activity that caused the nuisance, and specifying punishment for contempt if the defendant is in breach of such an injunction.The law and economics movement has been involved in analyzing the most efficient choice of remedies given the circumstances of the nuisance. In Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co. a cement plant interfered with a number of neighbors, yet the cost of complying with a full injunction would have been far more than a fair value of the cost to the plaintiffs of continuation. The New York court allowed the cement plant owner to 'purchase' the injunction for a specified amount—the permanent damages. In theory, the permanent damage amount should be the net present value of all future damages suffered by the plaintiff.

Inspector of Nuisances[edit]

An Inspector of Nuisances was the title of an office in several English-speaking jurisdictions. In many jurisdictions this term is now archaic, the position and/or term having been replaced by others. In medieval England it was an office of the Courts Leet and later it was also a parochial office concerned with local action against a wide range of 'nuisances' under the common law: obstructions of the highway, polluted wells, adulterated food, smoke, noise, smelly accumulations, eavesdropping, peeping toms, lewd behaviour, and many others. In the United Kingdom from the mid- 19th century this office became associated with solving public health and sanitation problems, with other types of nuisances being dealt with by the local constables.The first Inspector of Nuisances appointed by a UK local authority Health Committee was Thomas Fresh in Liverpool in 1844. Liverpool later promoted a private Act, the Liverpool Sanatory (sic) Act 1846, that created a statutory post of Inspector of Nuisances. This became the precedent for later local and national legislation. In local authorities that had established a Board of Health under the Public Health Act 1848, or under local Acts implementing the Towns Improvement Clauses Act of 1847, the title was 'Inspector of Nuisances'. The 1855 Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act and the Metropolis Management Act 1855 (via section 134) mandated such an office but with the title of 'Sanitary Inspector'. So in some places the title was 'Sanitary Inspector' and in others 'Inspector of Nuisances'. Eventually the title was standardized across all UK local authorities as 'Sanitary Inspector'. An Act of Parliament in 1956 changed the title to 'Public Health Inspector'. Similar offices were established across the British Commonwealth and Empire.

The nearest modern equivalent of this position in the UK is the Environmental Health Officer. This title being adopted by local authorities on the recommendation of Central Government after the Local Government Act 1972. Today, Registered UK Environmental Health Officers working in non-enforcement roles (e.g. in the private sector) may prefer to use the generic term 'Environmental Health Practitioner'.

In the United States, a modern example of an officer with the title 'Inspector of Nuisances' but not the public health role is found in Section 3767[7] of the Ohio Revised Code which defines such a position to investigate nuisances, where this term broadly covers establishments in which lewdness and alcohol are found. Whereas in the United States the environmental health officer role is undertaken by local authority officers with the titles 'Registered Environmental Health Specialist' or 'Registered Sanitarian' depending on the jurisdiction.

[edit]

United Kingdom[edit]

Main article: Nuisance in English law

The boundaries of the tort are potentially unclear, due to the public/private nuisance divide, and existence of the rule in Rylands v Fletcher. Writers such as John Murphy of the University of Manchester have popularised the idea that Rylands forms a separate, though related, tort. This is still an issue for debate, and is rejected by others (the primary distinction in Rylands concerns 'escapes onto land', and so it may be argued that the only difference is the nature of the nuisance, not the nature of the civil wrong.)Under English law, unlike US law, it is no defence that the claimant "came to the nuisance": the 1879 case of Sturges v Bridgman is still good law, and a new owner can bring a claim in nuisance for the existing activities of a neighbour. In February 2014 the UK Supreme Court ruling in the case of Coventry v Lawrence [6] prompted the launch of a campaign [7] to have the "coming to a nuisance" law overturned. Campaigners hold that established lawful activity continuing with planning permission and local residents' support should be accepted as part of the character of the area by any new residents coming to the locality.

United States[edit]

There is perhaps no more impenetrable jungle in the entire law than that which surrounds the word 'nuisance.' It has meant all things to all people, and has been applied indiscriminately to everything from an alarming advertisement to a cockroach baked in a pie. There is general agreement that it is incapable of any exact or comprehensive definition.

Prosser, W. Page; Keeton, W. Page (1984). Prosser and Keeton on Torts (5th ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota: West Publishing. §§ 86, 616. ISBN 978-0-314-74880-5.

There are two classes of nuisance under the American law: a nuisance in fact, or "nuisance per accidens", and a nuisance per se. The classification determines whether the claim goes to the jury, or gets decided by the judge. An alleged nuisance in fact is an issue of fact to be determined by the jury, who will decide whether the thing (or act) in question created a nuisance, by examining its location and surroundings, the manner of its conduct, and other circumstances.[8] A determination that something is a nuisance in fact also requires proof of the act and its consequences.[8]

By contrast, a nuisance per se is "an activity, or an act, structure, instrument, or occupation which is a nuisance at all times and under any circumstances, regardless of location or surroundings."[9] Liability for a nuisance per se is absolute, and injury to the public is presumed; if its existence is alleged and established by proof, it is also established as a matter of law.[10] Therefore, a judge would decide a nuisance per se, while a jury would decide a nuisance in fact.

Most nuisance claims allege a nuisance in fact, for the simple reason that not many actions or structures have been deemed to be nuisances per se. In general, if an act, or use of property, is lawful, or authorized by competent authority, it cannot be a nuisance per se.[11] Rather, the act in question must either be declared by public statute, or by case law, to be a nuisance per se.[12] There are few state or federal statutes or case law declaring actions or structures to be a nuisance in and of themselves. Few activities or structures, in and of themselves and under any and all circumstances, are a nuisance; which is how courts determine whether or not an action or structure is a nuisance per se.[13]

Over the last 1000 years, public nuisance has been used by governmental authorities to stop conduct that was considered quasi-criminal because, although not strictly illegal, it was deemed unreasonable in view of its likelihood to injure someone in the general public. Donald Gifford[14] argues that civil liability has always been an "incidental aspect of public nuisance".[15] Traditionally, actionable conduct involved the blocking of a public roadway, the dumping of sewage into a public river or the blasting of a stereo in a public park.[16] To stop this type of conduct, governments sought injunctions either enjoining the activity that caused the nuisance or requiring the responsible party to abate the nuisance.

In recent decades, however, governments blurred the lines between public and private nuisance causes of action. William Prosser noted this in 1966 and warned courts and scholars against confusing and merging the substantive laws of the two torts. In some states, his warning went unheeded and some courts and legislatures have created vague and ill-defined definitions to describe what constitutes a public nuisance. For example, Florida's Supreme Court has held that a public nuisance is any thing that causes "annoyance to the community or harm to public health."[17]

A contemporary example of a nuisance law in the United States is the Article 40 Bylaw of Amherst, Massachusetts known as the Nuisance House Bylaw. The law is voted on by members of the town at town meetings. The stated purpose of such a law is "In accordance with the Town of Amherst’s Home Rule Authority, and to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the inhabitants of the Town, this bylaw shall permit the Town to impose liability on owners and other responsible persons for the nuisances and harm caused by loud and unruly gatherings on private property and shall discourage the consumption of alcoholic beverages by underage persons at such gatherings."[18]

In practice, the law works so that if one member of the neighborhood feels that a neighbor's noise level is annoying or excessively loud, that neighbor is instructed to inform the town police so that they can respond to the location of the noise. "The responding officer has some discretion in how to deal with the noise complaint.... When determining the appropriate response, the officer may take many factors into consideration, such as the severity of the noise, the time of day, whether the residents have been warned before, the cooperation of the residents to address the problem."[19][20]

The term is also used less formally in the United States to describe the non-meritorious nature of frivolous litigation. A lawsuit may be described as a "nuisance suit", and a settlement a "nuisance settlement", if the defendant pays money to the plaintiff to drop the case primarily to spare the cost of litigation, rather than because the suit would have a significant likelihood of winning.

Environmental nuisance[edit]

In the field of environmental science, there are a number of phenomena which are considered nuisances under the law, including most notably noise and light pollution. Moreover there are some issues that are not necessarily legal matters that are termed environmental nuisance; for example, an excess population of insects or other vectors may be termed a "nuisance population" in an ecological sense.[21]From Britannica 1911[edit]

A common nuisance is punishable as a misdemeanour at common law, where no special provision is made by statute. In modern times, many of the old common law nuisances have been the subject of legislation. It's no defence for a master or employer that a nuisance is caused by the acts of his servants, if such acts are within the scope of their employment, even though such acts are done without his knowledge, and contrary to his orders. Nor is it a defence that the nuisance has been in existence for a great length of time, for no lapse of time will legitimate a public nuisance.[22]A private nuisance is an act, or omission, which causes inconvenience or damage to a private person, and is left to be redressed by action. There must be some sensible diminution of these rights affecting the value or convenience of the property. "The real question in all the cases is the question of fact, whether the annoyance is such as materially to interfere with the ordinary comfort of human existence" (Lord Romilly in Crump v. Lambert (1867) L.R. 3 Eq. 409). A private nuisance, differing in this respect from a public nuisance, may be legalized by uninterrupted use for twenty years. It used to be thought that, if a man knew there was a nuisance and went and lived near it, he couldn't recover, because, it was said, it is he that goes to the nuisance, and not the nuisance to him. But this has long ceased to be law, as regards both the remedy by damages, and the remedy by injunction.[22]

The remedy for a public nuisance is by information, indictment, summary procedure or abatement. An information lies in cases of great public importance, such as the obstruction of a navigable river by piers. In some matters, the law allows the party to take the remedy into his own hands, and to "abate" the nuisance. Thus; if a gate be placed across a highway, any person lawfully using the highway may remove the obstruction, provided that no breach of the peace is caused thereby. The remedy for a private nuisance is by injunction, action for damages or abatement. An action lies in every case for a private nuisance; it also lies where the nuisance is public, provided that the plaintiff can prove that he has sustained some special injury. In such a case, the civil is in addition to the criminal remedy. In abating a private nuisance, care must be taken not to do more damage than is necessary for the removal of the nuisance.[22]

In Scotland, there's no recognized distinction between public and private nuisances. The law as to what constitutes a nuisance is substantially the same as in England. A list of statutory nuisances will be found in the Public Health (Scotland) Act 1867, and amending acts. The remedy for nuisance is by interdict, or action.[22]

See also[edit]

- Aldred's Case

- Haslem v. Lockwood

- Law

- Public nuisance

- Robinson v Kilvert

- Rylands v. Fletcher

- Tort law

- William L. Prosser

- Loud music

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ Sir J. F. Stephen, Digest of the Criminal Law, p.120

- Jump up ^ Restatement (Second) of Torts § 821A cmt. b (1979). Originally developed as a private tort tied to the land, a nuisance action was generally brought when a person interfered with another's "use or enjoyment of land."

- Jump up ^ "William L. Prosser, Private Action for Public Nuisance, 52 Va. L. Rev. 997, 997 (1966)".

- Jump up ^ Restatement (Second) of Torts § 821B

- Jump up ^ Restatement (Second) of Torts § 821D

- Jump up ^ http://www.supremecourt.uk/decided-cases/docs/UKSC_2012_0076_Judgment.pdf

- Jump up ^ http://www.steamin.in/RDC/Petition.htm

- ^ Jump up to: a b City of Sunland Park v. Harris News, Inc., 2005-NMCA-128, 45, 124 P.3d 566, 138 N.M. 58 (citing 58 AM.JUR.2D NUISANCES § 21)

- Jump up ^ Id. 40 (citing State ex rel. Village of Los Ranchos v. City of Albuquerque, 119 N.M. 150, 164, 889 P.2d 185, 199 (1994))

- Jump up ^ See 58 AM.JUR.2D NUISANCES § 21

- Jump up ^ See 58 AM.JUR.2D NUISANCES § 20

- Jump up ^ State v. Davis, 65 N.M. 128, 132, 333 P.2d 613, 616 (1958); See also Sunland Park, 2005-NMCA-128, 47

- Jump up ^ Koeber, 72 N.M. at 5, 380 P.2d at 16.

- Jump up ^ "Donald G. Gifford", Research Professor of Law at the University of Maryland School of Law

- Jump up ^ Donald G. Gifford, Public Nuisance as a Mass Products Liability Tort, 71 U. Cin. L. Rev. 741, 781 (2003)

- Jump up ^ Restatement (Second) of Torts § 821A cmt. b (1979)

- Jump up ^ John Gray, "Public Nuisance Law: An Historical Perspective"

- Jump up ^ http://amherstnoise.weebly.com/nuisance-house-bylaw.html

- Jump up ^ http://amherstnoise.weebly.com/enforcement.html

- Jump up ^ http://www.amherstma.gov/DocumentView.aspx?DID=66

- Jump up ^ C.Michael Hogan, ed. 2010. American Kestrel. Encyclopedia of Earth, U.S. National Council for Science and the Environment, Ed-in-chief C.Cleveland

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Chisholm 1911, Nuisance.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nuisance". Encyclopædia Britannica 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nuisance". Encyclopædia Britannica 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links[edit]

| Look up nuisance in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "Public Nuisance Law": Essays and articles written by legal experts in the subject of public nuisance law.

Trespass

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Unlawful entry" redirects here. For the 1992 film, see Unlawful Entry (film).

For other uses, see Trespass (disambiguation).

| The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (April 2011) |

| Part of the common law series |

| Tort law |

|---|

| Intentional torts |

| Property torts |

| Defenses |

| Negligence |

| Liability torts |

| Nuisance |

| Dignitary torts |

| Economic torts |

| Liability and remedies |

| Duty to visitors |

| Other common law areas |

Trespass to the person historically involved six separate trespasses: threats, assault, battery, wounding, mayhem, and maiming.[1] Through the evolution of the common law in various jurisdictions, and the codification of common law torts, most jurisdictions now broadly recognize three trespasses to the person: assault, which is "any act of such a nature as to excite an apprehension of battery";[2] battery, "any intentional and unpermitted contact with the plaintiff's person or anything attached to it and practically identified with it";[2] and false imprisonment, the "unlaw[ful] obstruct[ion] or depriv[ation] of freedom from restraint of movement".[3]

Trespass to chattels, also known as trespass to goods or trespass to personal property, is defined as "an intentional interference with the possession of personal property … proximately caus[ing] injury".[4] Trespass to chattel does not require a showing of damages. Simply the "intermeddling with or use of … the personal property" of another gives cause of action for trespass.[5][6] Since CompuServe Inc. v. Cyber Promotions,[7] various courts have applied the principles of trespass to chattel to resolve cases involving unsolicited bulk e-mail and unauthorized server usage.[8][9][10][11]

Trespass to land is today the tort most commonly associated with the term trespass; it takes the form of "wrongful interference with one's possessory rights in [real] property".[12] Generally, it is not necessary to prove harm to a possessor's legally protected interest; liability for unintentional trespass varies by jurisdiction. "[A]t common law, every unauthorized entry upon the soil of another was a trespasser"; however, under the tort scheme established by the Restatement of Torts, liability for unintentional intrusions arises only under circumstances evincing negligence or where the intrusion involved a highly dangerous activity.[13]

Trespass has also been treated as a common law offense in some countries.

Contents

[hide]Trespass to the person[edit]

There are three types of trespass, the first of which is trespass to the person. Whether intent is a necessary element of trespass to the person varies by jurisdiction. Under English decision, Letang v Cooper,[14] intent is required to sustain a trespass to the person cause of action; in the absence of intent, negligence is the appropriate tort. In other jurisdictions, gross negligence is sufficient to sustain a trespass to the person, such as when a defendant negligently operates an automobile and strikes the plaintiff with great force. "Intent is to be presumed from the act itself."[15] Generally, trespass to the person consists of three torts: assault, battery, and false imprisonment.Assault[edit]

Main article: Assault (tort)

Under the statutes of various common law jurisdictions, assault is both a crime and a tort. Generally, a person commits criminal assault if he purposely, knowingly, or recklessly inflicts bodily injury upon another; if he negligently inflicts bodily injury upon another by means of dangerous weapon; or if through physical menace, he places another in fear of imminent serious bodily injury.[16] A person commits tortious assault when he engages in "any act of such a nature as to excite an apprehension of battery [bodily injury]".[2] In some jurisdictions, there is no requirement that actual physical violence result—simply the "threat of unwanted touching of the victim" suffices to sustain an assault claim.[17] Consequently, in R v Constanza,[18] the court found a stalker's threats could constitute assault. Similarly, silence, given certain conditions, may constitute an assault as well.[19] However, in other jurisdictions, simple threats are insufficient; they must be accompanied by an action or condition to trigger a cause of action.[20]Incongruity of a defendant's language and action, or of a plaintiff's perception and reality may vitiate an assault claim. In Tuberville v Savage,[21] the defendant reached for his sword and told the plaintiff that "[i]f it were not assize-time, I would not take such language from you". In its American counterpart, Commonwealth v. Eyre,[22] the defendant shouted "[i]f it were not for your gray hairs, I would tear your heart out". In both cases, the courts held that despite a threatening gesture, the plaintiffs were not in immediate danger. The actions must give the plaintiff a reasonable expectation that the defendant is going to use violence; a fist raised before the plaintiff may suffice; the same fist raised behind the window of a police cruiser will not.[23]

Battery[edit]

Main article: Battery (tort)

Battery is "any intentional and unpermitted contact with the plaintiff's person or anything attached to it and practically identified with it". The elements of battery common law varies by jurisdiction. In the United States, the American Law Institute's Restatement of Torts provides a general rule to determine liability for battery:[24]An act which, directly or indirectly, is the legal cause of a harmful contact with another's person makes the actor liable to the other, if:Battery torts under Commonwealth precedent are subjected to a four point test to determine liability:[25]

(a) the act is done with the intention of bringing about a harmful or offensive contact or an apprehension thereof to the other or a third person, and

(b) contact is not consented to by the other or the other's consent thereto is procured by fraud or duress, and

(c) the contact is not otherwise privileged.

- Directness. Is the sequence of events connecting initial conduct and the harmful contact an unbroken series?[26]

- Intentional Act. Was the harmful contact the conscious object of the defendant? Did the defendant intend to cause the resulting harm? Though the necessity of intent remains an integral part of Commonwealth battery,[27] some Commonwealth jurisdictions have moved toward the American jurisprudence of "substantial certainty".[28] If a reasonable person in the defendant's position would apprehend the substantial certainty of the consequences of his actions, whether the defendant intended to inflict the injuries is immaterial.[28]

- Bodily Contact. Was there active (as opposed to passive) contact between the bodies of the plaintiff and the defendant?

- Consent. Did the plaintiff consent to the harmful contact? The onus is on the defendant to establish sufficient and effective consent.[29][30]

False imprisonment[edit]

Main article: False imprisonment

False imprisonment is defined as "unlaw[ful] obstruct[ion] or depriv[ation] of freedom from restraint of movement".[3] In some jurisdictions, false imprisonment is a tort of strict liability: no intention on the behalf of the defendant is needed, but others require an intent to cause the confinement.[31] Physical force, however, is not a necessary element,[32] and confinement need not be lengthy;[33][34] the restraint must be complete,[35] though the defendant needn't resist.[36]Conveniently, the American Law Institute's Restatement (Second) of Torts distills false imprisonment liability analysis into a four-prong test:

- The defendant intends to confine the plaintiff. (This is not necessary in Commonwealth jurisdictions.)

- The plaintiff is conscious of the confinement. (Prosser rejects this requirement.)[37]

- The plaintiff does not consent to the confinement.

- The confinement was not otherwise privileged.

Defenses[edit]

Child correction[edit]

Depending on the jurisdiction, corporal punishment of children by parents or instructors may be a defense to trespass to the person, so long as the punishment was "reasonably necessary under the circumstances to discipline a child who has misbehaved" and the defendant "exercise[d] prudence and restraint".[38] Unreasonable punishments, such as violently grabbing a student's arm and hair, have no defense.[39] Many jurisdictions, however, limit corporal punishment to parents, and a few, such as New Zealand, have criminalized the practice.[40]Consent[edit]

Denning, LJ: "[I]n an ordinary fight with fists there is no cause of action to either of [the combatants] for any injury suffered."

Medical care gives rise to many claims of trespass to the person. A physician, "treating a mentally competent adult under non-emergency circumstances, cannot properly undertake to perform surgery or administer other therapy without the prior consent of his patient".[47] Should he do so, he commits a trespass to the person and is liable to damages. However, if the plaintiff is informed by a doctor of the broad risks of a medical procedure, there will be no claim under trespass against the person for resulting harm caused; the plaintiff's agreement constitutes "informed consent".[48] In those cases where the patient does not possess sufficient mental capacity to consent, doctors must exercise extreme caution. In F v West Berkshire Health Authority,[49] the House of Lords instructed British physicians that, to justify operating upon such an individual, there "(1) must … be a necessity to act when it is not practicable to communicate with the assisted person ... [and] (2) the action taken must be such as a reasonable person would in all the circumstances take, acting in the best interests of the assisted person".

Self-defense / defense of others / defense of property[edit]

Self-defense, or non-consensual privilege, is a valid defense to trespasses against the person, assuming that it constituted the use of "reasonable force which they honestly and reasonably believe is necessary to protect themselves or someone else, or property".[50] The force used must be proportionate to the threat, as ruled in Cockcroft v Smith.[51]Trespass to chattels[edit]

Main article: Trespass to chattels

Trespass to chattels, also known as trespass to goods or trespass to personal property, is defined as "an intentional interference with the possession of personal property...proximately caus[ing] injury".[4] While originally a remedy for the asportation of personal property, the tort grew to incorporate any interference with the personal property of another.[52] In some jurisdictions, such as the United Kingdom[dubious ], trespass to chattels has been codified to clearly define the scope of the remedy;[53][54] in most jurisdictions, trespass to chattel remains a purely common law remedy, the scope of which varies by jurisdiction.Generally, trespass to chattels possesses three elements:

- Lack of consent. The interference with the property must be non-consensual. A claim does not lie if, in acquiring the property, the purchaser consents contractually to certain access by the seller. "[A]ny use exceeding the consent" authorized by the contract, should it cause harm, gives rise to a cause for action.[55]

- Actual harm. The interference with the property must result in actual harm.[7] The threshold for actual harm varies by jurisdiction. In California, for instance, an electronic message may constitute a trespass if the message interferes with the functioning of the computer hardware, but the plaintiff must prove that this interference caused actual hardware damage or actual impaired functioning.[56]

- Intentionality. The interference must be intentional. What constitutes intention varies by jurisdiction, however, the Restatement (Second) of Torts indicates that "intention is present when an act is done for the purpose of using or otherwise intermeddling with a chattel or with knowledge that such an intermeddling will, to a substantial certainty, result from the act", and continues: "[i]t is not necessary that the actor should know or have reason to know that such intermeddling is a violation of the possessory rights of another".[57]

Traditional applications[edit]

Trespass to chattels typically applies to tangible property and allows owners of such property to seek relief when a third party intentionally interferes or intermeddles in the owner's possession of his personal property.[59] "Interference" is often interpreted as the "taking" or "destroying" of goods, but can be as minor as "touching" or "moving" them in the right circumstances. In Kirk v Gregory,[60] the defendant moved jewelry from one room to another, where it was stolen. The deceased owner's executor successfully sued her for trespass to chattel. Furthermore, personal property, as traditionally construed, includes living objects, except where property interests are restricted by law. Thus animals are personal property,[61] but organs are not.[62]Modern US applications[edit]

To date, no United States court has identified property rights in items acquired in virtual worlds; heretofore, virtual world providers have relied on end-user license agreements to govern user behavior.[68] Nevertheless, as virtual worlds grow, incidents of property interference, a form of "griefing", may make trespass to chattel an attractive remedy for deleted, stolen, or corrupted virtual property.[58]

Trespass to land[edit]

Main article: Trespass to land

Trespass to land involves the "wrongful interference with one's possessory rights in [real] property."[12] It is not necessary to prove that harm was suffered to bring a claim, and is instead actionable per se. While most trespasses to land are intentional, British courts have held liability holds for trespass committed negligently.[69] Similarly, some American courts will find liability for unintentional intrusions only where such intrusions arise under circumstances evincing negligence or involve a highly dangerous activity.[13] Exceptions exist for entering land adjoining a road unintentionally (such as in a car accident), as in River Wear Commissioners v Adamson.[70] In some jurisdictions trespass while in possession of a firearm, which may include a low-power air weapon without ammunition, constitutes a more grave crime of armed trespass.[71]Subsoil and airspace[edit]

Aside from the surface, land includes the subsoil, airspace and anything permanently attached to the land, such as houses, and other infrastructure, this is literally explained by the legal maxim quicquid plantatur solo, solo cedit.Subsoil[edit]

William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England articulated the common law principle cuius est solum eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos, translating from Latin as "for whoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to Heaven and down to Hell."[72] In modern times, courts have limited the right of absolute dominion over the subsurface. For instance, drilling a directional well that bottoms out beneath another's property to access oil and gas reserves is trespass,[73] but a subsurface invasion by hydraulic fracturing is not.[74] Where mineral rights are severed from surface ownership, it is trespass to use another's surface to assist in mining the minerals beneath that individual's property,[75] but, where an emergency responder accesses the subsurface following a blowout and fire, no trespass lies.[76] Even the possible subsurface migration of toxic waste stored underground is not trespass,[77] except where the plaintiff can demonstrate that the actions "actually interfere with the [owner's] reasonable and foreseeable use of the subsurface[,]"[78] or, in some jurisdictions, that the subsurface trespasser knows with "substantial certainty" that the toxic liquids will migrate to the neighboring land...[79]Airspace[edit]

Douglas, J: " [E]very transcontinental flight would subject the operator to countless trespass suits."

Interference[edit]

The main element of the tort is "interference". This must be both direct and physical, with indirect interference instead being covered by negligence or nuisance.[88] "Interference" covers any physical entry to land, as well as the abuse of a right of entry, when a person who has the right to enter the land does something not covered by the permission. If the person has the right to enter the land but remains after this right expires, this is also trespass. It is also a trespass to throw anything on the land.[89] For the purposes of trespass, the person who owns the land on which a road rests is treated as the owner; it is not, however, a trespass to use that road if the road is constructed with a public use easement, or if, by owner acquiescence or through adverse use, the road has undergone a common law dedication to the public.[90] In Hickman v Maisey[91] and Adams v. Rivers,[92] the courts established that any use of a road that went beyond using it for its normal purpose could constitute a trespass: "[a]lthough a land owner's property rights may be [s]ubject to the right of mere passage, the owner of the soil is still absolute master."[93] British courts have broadened the rights encompassed by public easements in recent years. In DPP v Jones,[94] the court ruled that "the public highway is a public place which the public may enjoy for any reasonable purpose, providing that the activity in question does not amount to a public or private nuisance and does not obstruct the highway by reasonably impeding the primary right of the public to pass and repass; within these qualifications there is a public right of peaceful assembly on the highway."[95] The principles established in Adams remain valid in American law.[93][96]Defenses[edit]

There are several defenses to trespass to land; license, justification by law, necessity and jus tertii. License is express or implied permission, given by the possessor of land, to be on that land. These licenses are irrevocable unless there is a flaw in the agreement or it is given by a contract. Once revoked, a license-holder becomes a trespasser if they remain on the land. Justification by law refers to those situations in which there is statutory authority permitting a person to go onto land, such as the England and Wales' Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, which allows the police to enter land for the purposes of carrying out an arrest, or the California state constitution, which permits protests on grocery stores and strip malls, despite their presenting a general nuisance to store owners and patrons.[97] Jus tertii is where the defendant can prove that the land is not possessed by the plaintiff, but by a third party, as in Doe d Carter v Barnard.[98] This defense is unavailable if the plaintiff is a tenant and the defendant a landlord who had no right to give the plaintiff his lease (e.g. an illegal apartment rental, an unauthorized sublet, etc.).[99] Necessity is the situation in which it is vital to commit the trespass; in Esso Petroleum Co v Southport Corporation,[100] the captain of a ship committed trespass by allowing oil to flood a shoreline. This was necessary to protect his ship and crew, however, and the defense of necessity was accepted.[101] Necessity does not, however, permit a defendant to enter another's property when alternative, though less attractive, courses of action exist.[102]See also[edit]

- Appropriation (economics)

- Trespass on the case

- Trespass in English law

- Castle Doctrine

- Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (UK)

- Forced entry

- Freedom to roam

- Easement

- Structural encroachment

- Rights of way in England and Wales

- Rights of way in Scotland

- Property is theft!

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ Underhill and Pease, p. 242

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Johnson v. Glick, 481 F.2d 1028, 1033 (2nd Cir. 1973)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broughton v. New York, 37 N.Y.2d 451, 456–7

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thrifty-Tel, Inc., v. Bezenek, 46 Cal. App. 4th 1559, 1566–7

- Jump up ^ Thrifty-Tel, at 1567

- Jump up ^ Restatement (Second) of Torts § 217(b)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c 962 F. Supp. 1015 (S.D.Ohio 1997)

- Jump up ^ America Online, Inc., v. LCGM, Inc., 46 F. Supp.2d 444 (E.D.Vir. 1998)

- ^ Jump up to: a b America Online, Inc. v. IMS, 24 F. Supp.2d 548 (E.D.Vir. 1998)

- Jump up ^ eBay, Inc., v. Bidder's Edge, Inc., 100 F. Supp.2d 1058 (N.D.Cal. 2000)

- Jump up ^ Register.com, Inc., v. Verio, Inc., 126 F. Supp.2d 238 (S.D.N.Y. 2000)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robert's River Rides v. Steamboat Dev., 520 N.W.2d 294, 301 (Iowa 1994)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Loe et ux. v. Lenhard et al., 362 P.2d 312 (Or. 1961)

- Jump up ^ [1964] 2 All ER 292 (CA)

- Jump up ^ Myers v. Baker, 387 So 643, 644 (Ala. Ct. App. 1931) qtd. in McKenzie v. Killian, 887 So.2d 861, 865 (Ala. 2004) (An automobile accident occurring wrongfully and with great force constitutes a trespass if facts prove an intentional or grossly negligent act. Intent is presumed from the act itself.)

- Jump up ^ Summary of Model Penal Code § 211.1 (simple assault)

- Jump up ^ Banks v. Fritsch, 39 S.W.3d 474, 480 (Ky. Ct. App. 2001)

- Jump up ^ [1997] EWCA Crim 633

- Jump up ^ R v Ireland [1997] UKHL 34

- Jump up ^ People v. Floyd, 537 N.E.2d 74 (Ill. App. 1996)

- Jump up ^ [1669] 1 Mod Rep 3, 86 ER 684 (KB)

- Jump up ^ 1 Serg & R (Pa.) 3478 (1815)

- Jump up ^ Elliott, p. 301.

- Jump up ^ 1 Restatement of Torts 29 § 13

- Jump up ^ Trinidade, p. 216

- Jump up ^ Scott v Shepherd [1773] 2 Wm Bl 892, (1773) 95 ER 1124 (K.B.)

- Jump up ^ Law of Torts, 5th ed (1977) 24, n. 26

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trinidade, p. 221

- Jump up ^ Schweizer v Central Hospital (1974) OR (2d) 606, 53 DLR (3d) 494 (Ont HC)

- Jump up ^ Kelly v Hazlett (1976) 75 DLR (3d) 536 (Ont HC)

- Jump up ^ Restatement (Second) of Torts § 44 (1965)

- Jump up ^ Schanafelt v. Seaboard Finance Co., 108 Cal. App. 2d 420, 422–423 (A judgment against a finance company was upheld after a company employee used false imprisonment in repossession of plaintiff's furniture for payment delinquency, instructing the plaintiff she must remain in her home and could not leave.)

- Jump up ^ Alterauge v. Los Angeles Turf Club, 218 P.2d 802 (Cal. Ct. App. 1950) (A detention of the plaintiff for fifteen minutes by track detectives searching for evidence of bookmaking was held to constitute false imprisonment.)

- Jump up ^ Austin & Anor v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis [2007] EWCA Civ 989 (Seven hours of police detention constitutes false imprisonment.)

- Jump up ^ Bird v Jones [1845] 7 QB 742 (The partial obstruction of a footpath ordinarily traversed by the plaintiff is not sufficient to sustain a claim of false imprisonment, as alternative paths existed.)

- Jump up ^ Grainger v Hill, (1838) 4 Bing (NC) 212

- Jump up ^ Torts [4th ed], § 11

- Jump up ^ Ingraham v. Wright, 430 U.S. 651, 676-7

- Jump up ^ Garcia by Garcia v. Miera, 817 F.2d 650, 655–6 (10th Cir. 1987)

- Jump up ^ Crimes (Substituted Section 59) Amendment Act 2007

- Jump up ^ 345 So.2d 1216, 1219–20 (La.App. 1977)

- Jump up ^ [2000] EWCA Civ 2116

- Jump up ^ Lane v Holloway [1967] EWCA Civ 1 [3]

- Jump up ^ Reinertsen v. Rygg, No. 55831-1-I

- Jump up ^ Hudson v. Craft, 33 Cal.2d 654, 656

- Jump up ^ State v. Mackrill, 191 P.3d 451, 457 (Mont. 2008)

- Jump up ^ Sard v. Hardy, 281 Md. 432, 439

- Jump up ^ Chatterton v. Gerson [1981] 1 All ER 257 (QB)

- Jump up ^ [1989] 2 All ER 545, 565–66

- Jump up ^ Elliott, p. 308

- Jump up ^ [1705] 2 Salk 642

- Jump up ^ Thrifty-Tel, Inc., at 1566

- Jump up ^ Torts (Interference with Goods) Act 1977

- Jump up ^ Elliott, p. 314

- Jump up ^ Restatement (Second) of Torts § 256 (1965)

- Jump up ^ Intel Corp. v. Hamidi, 71 P.3d 296 (Cal. 2003)

- Jump up ^ Restatement (Second) of Torts § 217 (1965)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ledgerwood, p. 848

- Jump up ^ Ledgerwood, p. 847

- Jump up ^ [1876] 1 Ex D 55

- Jump up ^ Slater v Swann [1730] 2 Stra 872

- Jump up ^ AB & Ors v Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust [2004] EWHC 644 (QB)

- Jump up ^ " [T]he electronic signals generated by the [defendants'] activities were sufficiently tangible to support a trespass cause of action." Thrifty-Tel v. Bezenek, 46 Cal.App.4th 1559, n. 6 54 Cal.Rptr.2d 468 (1996)

- Jump up ^ 46 F. Supp.2d 444 (N.D.Vir. 1998)

- Jump up ^ 100 F. Supp.2d 1058 (N.D.Cal. 2000)

- Jump up ^ Bidder's Edge, at 1070

- Jump up ^ 71 P.3d 296 (Cal. 2003)

- Jump up ^ Ledgerwood, p. 813

- Jump up ^ League Against Cruel Sports v Scott [1985] 2 All ER 489

- Jump up ^ (1877) 2 App Cas 743

- Jump up ^ Marple Rifle & Pistol Club, Gun Law in the UK

- Jump up ^ Sprankling, pp. 282–83

- Jump up ^ Anderson, p. 254

- Jump up ^ Anderson, p. 258

- Jump up ^ Anderson, p. 264

- Jump up ^ Anderson, p. 268

- Jump up ^ Anderson, p. 269

- Jump up ^ Anderson, p. 271

- Jump up ^ Anderson, p. 272

- Jump up ^ 328 U.S. 256, 260 (1946)

- Jump up ^ 49 U.S.C. § 40103

- Jump up ^ [1977] EWHC 1 (QB)

- Jump up ^ Berstein, at [4]

- Jump up ^ Elliott, p. 320

- Jump up ^ [1970] 1 WLR 411

- Jump up ^ [1957] 2 QB 334

- Jump up ^ Anderson, p. 255

- Jump up ^ Smith, p. 513

- Jump up ^ Elliott, p. 321

- Jump up ^ Gion v. City of Santa Cruz, 2 Cal.3d 29, 38

- Jump up ^ [1900] 1 QB 752

- Jump up ^ 11 Barb. (N.Y.) 390 (1851)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berns v. Doan, 961 A.2d 506, 510 (Del. 2008) (internal quotes omitted)

- Jump up ^ [1999] 2 AC 240

- Jump up ^ Elliott, p. 322

- Jump up ^ City of Los Angeles v. Pac. Elec. Ry. Co., Cal.App.2d 224, 229

- Jump up ^ Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins, 447 U.S. 74 (1980)

- Jump up ^ [1849] 13 QB 945;

- Jump up ^ Elliott, p. 324

- Jump up ^ [1956] AC 28

- Jump up ^ Elliott, p. 325

- Jump up ^ Berns, at 505

Bibliography[edit]

Books[edit]

- Elliott, Catherine; Francis Quinn (2007). Tort Law (6th ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-4672-1.

- Smith, Kenneth; Denis J. Keenan (2004). English Law (14th ed.). Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 0-582-82291-2.

Periodicals[edit]

- Anderson, Owen L. (2010). "Subsurface "Trespass": A Man's Subsurface is Not His Castle". Washburn L.J. 49.

- Ledgerwood, Garrett (2009). "Virtually Liable". Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 66.

- Trinidade, F.A. (1982). "Intentional Torts: Some Thoughts Assault and Battery". Oxford J. Legal Stud. 2 (2).

External links[edit]

- Criminal Trespass - Indian Penal Code (Mobile Friendly)

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Trespass |

Principles of grouping

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs attention from an expert in Cognitive science. (April 2011) |

Irvin Rock and Steve Palmer, who are acknowledged as having built upon the work of Max Wertheimer and others and to have identified additional grouping principles,[5] note that Werheimer's laws have come to be called the "Gestalt laws of grouping" but state that "perhaps a more appropriate description" is "principles of grouping."[6][7]

Contents

[hide]Proximity[edit]

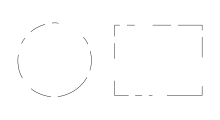

The Gestalt law of proximity states that "objects or shapes that are close to one another appear to form groups". Even if the shapes, sizes, and objects are radically different, they will appear as a group if they are close together. • refers to the way smaller elements are "assembled" in a composition.• Also called "grouping," the principle concerns the effect generated when the collective presence of the set of elements becomes more meaningful than their presence as separate elements.

• Arranging words into sentences or titles is an obvious way to group unrelated elements to enhance their meaning (it also depends on a correct order for comprehension). • Grouping the words also changes the visual and psychological meaning of the composition in non-verbal ways unrelated to their meaning. • Elements which are grouped together create the illusion of shapes or planes in space, even if the elements are not touching.

• Grouping of this sort can be achieved with: Tone / value Color Shape Size Or other physical attributes[citation needed]

Similarity[edit]

The principle of similarity states that, all else being equal, perception lends itself to seeing stimuli that physically resemble each other as part of the same object, and stimuli that are different as part of a different object. This allows for people to distinguish between adjacent and overlapping objects based on their visual texture and resemblance. Other stimuli that have different features are generally not perceived as part of the object. Our brain uses similarity to distinguish between objects who may lay adjacent to or overlap with each other based upon their visual texture. An example of this is a large area of land used by numerous independent farmers to grow crops. Each farmer may use a unique planting style which distinguishes his field from another. Another example is a field of flowers which differ only by color.[citation needed]Closure[edit]

The principle of closure refers to the mind’s tendency to see complete figures or forms even if a picture is incomplete, partially hidden by other objects, or if part of the information needed to make a complete picture in our minds is missing. For example, if part of a shape’s border is missing people still tend to see the shape as completely enclosed by the border and ignore the gaps. This reaction stems from our mind’s natural tendency to recognize patterns that are familiar to us and thus fill in any information that may be missing.Closure is also thought to have evolved from ancestral survival instincts in that if one was to partially see a predator their mind would automatically complete the picture and know that it was a time to react to potential danger even if not all the necessary information was readily available.

Good Continuation[edit]

When there is an intersection between two or more objects, people tend to perceive each object as a single uninterrupted object. This allows differentiation of stimuli even when they come in visual overlap. We have a tendency to group and organize lines or curves that follow an established direction over those defined by sharp and abrupt changes in direction...[citation needed]Common Fate[edit]

This allows people to make out moving objects even when other details (such as the objects color or outline) are obscured. This ability likely arose from the evolutionary need to distinguish a camouflaged predator from its background.

The law of common fate is used extensively in user-interface design, for example where the movement of a scrollbar is synchronised with the movement (i.e. cropping) of a window's content viewport; The movement of a physical mouse is synchronised with the movement of an on-screen arrow cursor, and so on.

Good Form[edit]

The principle of good form refers to the tendency to group together forms of similar shape, pattern, color, etc. Even in cases where two or more forms clearly overlap, the human brain interprets them in a way that allows people to differentiate different patterns and/or shapes. An example would be a pile of presents where a dozen packages of different size and shape are wrapped in just three or so patterns of wrapping paper.See also[edit]

- Global precedence

- Neural processing for individual categories of objects

- Perception

- Structural information theory

- Theory of indispensable attributes

- Pattern recognition

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ cf. Gray, Peter O. (2006): Psychology, 5th ed., New York: Worth, p. 281. ISBN 978-0-7167-0617-5

- Jump up ^ Wolfe et al. 2008, pp. 78,80.

- Jump up ^ Goldstein 2009, pp. 105–107.

- Jump up ^ Banerjee 1994, pp. 107–108.

- Jump up ^ Weiten 1998, pp. 144.

- Jump up ^ Palmer, Neff & Beck 1997, pp. 63.

- Jump up ^ Palmer 2003, pp. 180–181.

Bibliography[edit]

- Banerjee, J. C. (1994). "Gestalt Theory of Perception". Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Psychological Terms. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 107–109. ISBN 978-81-85880-28-0.

- Goldstein, E. Bruce (2009). "Perceiving Objects and Scenes § The Gestalt Approach to Object Perception". Sensation and perception (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-60149-4.

- Palmer, Stephen; Neff, Jonathan; Beck, Diane (1997). "Grouping and Amodal Perception". In Rock, Irvin. Indirect perception. MIT Press/Bradford Books series in cognitive psychology. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-18177-8.

- Palmer, Stephen E. (2003). "Visual Perception of Objects". In Healy, Alice F.; Proctor, Robert W.; Weiner, Irving B. Handbook of Psychology: Experimental psychology 4. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-39262-0.

- Weiten, Wayne (1998). Psychology: themes and variations (4th ed.). Brooks/Cole Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-534-34014-8.

- Wolfe, Jeremy M.; Kluender, Keith R.; Levi, Dennis M.; Bartoshuk, Linda M.; Herz, Rachel S.; Klatzky, Roberta L.; Lederman, Susan J. (2008). "Gestalt Grouping Principles". Sensation and Perception (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-938-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Enns, James T. (2003): Gestalt Principles of Perception. In: Lynn Nadel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, London: Nature Publishing Group.

- Todorovic, Dejan (2008). "Gestalt principles". Scholarpedia 3 (12): 5345. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.5345.

- Palmer, S.E. (1999). Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-16183-1.

Certification

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Certify" redirects here. For the horse, see Certify (horse).

"Certified" redirects here. For other uses, see Certified (disambiguation).

Certification refers to the confirmation of certain characteristics of an object, person, or organization. This confirmation is often, but not always, provided by some form of external review, education, assessment, or audit. Accreditation is a specific organization's process of certification.Contents

[hide]Types[edit]

One of the most common types of certification in modern society is professional certification, where a person is certified as being able to competently complete a job or task, usually by the passing of an examination and/or the completion of a program of study. Some professional certifications also require that one obtain work experience in a related field before the certification can be awarded. Some professional certifications are valid for a lifetime upon completing all certification requirements. Others expire after a certain period of time and have to be maintained with further education and/or testing.Certifications can differ within a profession by the level or specific area of expertise to which they refer. For example, in the IT Industry there are different certifications available for software tester, project manager, and developer. Also, the Joint Commission on Allied Health Personnel in Ophthalmology offers three certifications in the same profession, but with increasing complexity.

Certification does not designate that a person has sufficient knowledge in a subject area, only that they passed the test.[1]

Certification does not refer to the state of legally being able to practice or work in a profession. That is licensure. Usually, licensure is administered by a governmental entity for public protection purposes and a professional association administers certification. Licensure and certification are similar in that they both require the demonstration of a certain level of knowledge or ability.

Another common type of certification in modern society is product certification. This refers to processes intended to determine if a product meets minimum standards, similar to quality assurance. Different certification systems exist in each country. For example, in Russia it is the GOST R Rostest.

Third-party certification[edit]

In first-party certification, an individual or organization providing the good or service offers assurance that it meets certain claims. In second-party certification, an association to which the individual or organization belongs provides the assurance.[2] Third-party certification involves an independent assessment declaring that specified requirements pertaining to a product, person, process or management system have been met.[3] In this respect, a Notified Body is a third-party, accredited body which is entitled by an Accreditation Body. Upon definition of standards and regulations, the Accreditation Body may allow a Notified Body to provide third-party certification and testing services. All this in order to ensure and assess compliance to the previously defined codes, but also to provide an official certification mark or a declaration of conformity.[4][5]Certification in software testing[edit]

For software testing the certifications can be grouped into exam-based and education-based. Exam-based certifications: For this there is the need to pass an exam, which can also be learned by self-study: e.g. for International Software Testing Qualifications Board Certified Tester by the International Software Testing Qualifications Board [6] or Certified Software Tester by QAI or Certified Software Quality Engineer by American Society for Quality. Education-based certifications are the instructor-led sessions, where each course has to be passed, e.g. Certified Software Test Professional or Certified Software Test Professional by International Institute for Software Testing.[7][8]Types of certification[edit]

- Academic degree[9]

- Professional certification

- Product certification and certification marks

- Cyber security certification

- Digital signatures in public-key cryptography

- Digital certification

- Music recording sales certification, such as "Gold" or "Platinum"

- Film certification, also known as Motion picture rating system [10]

- Professional certification (computer technology)

- Diving certification

- Laboratory Certification and audits [11]

- Environmental certification

- A Type certificate is issued to signify the airworthiness of an aircraft manufacturing design

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ Cem Kaner. "Why propose an advanced certification in software testing?". Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Jump up ^ Dovetail Partners

- Jump up ^ "ANSI". Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Jump up ^ "Boiler and Pressure Vessel Inspection According to ASME". Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Jump up ^ "NABL Certified Lab". Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Jump up ^ "Certifying Software Testers Worldwide - ISTQB® International Software Testing Qualifications Board". Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Jump up ^ "International Institute for Software Testing (IIST) CSTP & CTM Informational Home Page". Testinginstitute.com. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- Jump up ^ "Certifying Software Testers Worldwide - ISTQB® International Software Testing Qualifications Board". Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Jump up ^ "Academic Degrees Abbreviations". Abbreviations.com. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- Jump up ^ http://www.mpaa.org/

- Jump up ^ "Certifications". Caslab.com. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

External links[edit]

- Institute for Credentialing Excellence (ICE): The ICE Basic Guide to Credentialing Terminology (2006) and The ICE Guide to Understanding Credentialing Concepts (2005)

- International Certification Accreditation Council (ICAC)

- Forest Certification Center (Metafore)

- American National Standards Institute

- International Organization for Standardization

- Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC)

|

EVALUATION-

CONSERVATORSHIP LAWS

SCOPE OF TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE RESEARCH-

SCOPE OF COUNTRIES

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

GERMANY IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

OBSERVATIONAL

LEARNING

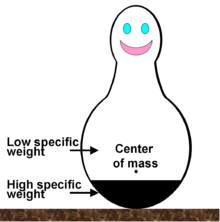

OBSERVATIONAL LEARNING IS THE MEDICAL

TREATMENT TO GRAVELY MENTAL

DISABILITY .

Observational learning

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Social learning (disambiguation).